The Da Vinci Code has finally made it to cinema screens, and "behold, the greatest cover-up in human history" has finally been revealed. Whilst critics of the book have slated it for a myriad of errors, even including its title (calling Leonardo "Da Vinci" is like calling Jesus "of Nazareth"), the film has gone one step further. Even its creators think it's bad. So bad, in fact, that even the very top critics only got their first glimpse of it at the Cannes Film Festival on Wednesday - two days before its general release. The film is of course bullet-proof. Like Star Wars Episode III, it doesn't matter how much the critics pan it, it will still be a box office smash. But I can't help wondering if there is a conspiracy going on when film-makers cover-up their films to prevent "the truth" from getting out.

The Da Vinci Code has finally made it to cinema screens, and "behold, the greatest cover-up in human history" has finally been revealed. Whilst critics of the book have slated it for a myriad of errors, even including its title (calling Leonardo "Da Vinci" is like calling Jesus "of Nazareth"), the film has gone one step further. Even its creators think it's bad. So bad, in fact, that even the very top critics only got their first glimpse of it at the Cannes Film Festival on Wednesday - two days before its general release. The film is of course bullet-proof. Like Star Wars Episode III, it doesn't matter how much the critics pan it, it will still be a box office smash. But I can't help wondering if there is a conspiracy going on when film-makers cover-up their films to prevent "the truth" from getting out.So, having decided to see and review the film, it was something of a relief to find that it was not as bad as I'd been lead to believe. It's no classic of course, but on the whole it's a reasonably entertaining thriller as Dan Brown's novel is. It's unlikely to do as well as the book - its opening night was only 12th in the list of biggest first nights, and it's difficult to imagine that word of mouth will give it a long cinema run, particularly given the critical slating it has received.

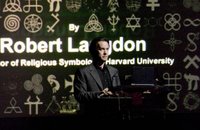

For those who are still unaware of the plot, the following should provide a rough overview. Harvard Professor of Symbology Robert Langdon (Tom Hanks) is summoned to the scene of a murder in the Louvre - the corpse in question being its curator Jacques Saunière who was due to meet Langdon around the time of his death. This, and the strange clues left by the dying curator, lead the police to suspect that Langdon is the killer. We of course know different because not only do we witness the murder, but we all know that nice Tom Hanks would never murder anyone. Instead, we're encouraged to identify with him through a number of camera shots from his point of view.

For those who are still unaware of the plot, the following should provide a rough overview. Harvard Professor of Symbology Robert Langdon (Tom Hanks) is summoned to the scene of a murder in the Louvre - the corpse in question being its curator Jacques Saunière who was due to meet Langdon around the time of his death. This, and the strange clues left by the dying curator, lead the police to suspect that Langdon is the killer. We of course know different because not only do we witness the murder, but we all know that nice Tom Hanks would never murder anyone. Instead, we're encouraged to identify with him through a number of camera shots from his point of view.Langdon is promptly rescued by Sophie Neveu who is played by Audrey Tautou (Amélie) who also turns out to be the dead curator's estranged Granddaughter. Hence the two of them flee police captain Fache (Jean Reno) and try to find out why Saunière died and why. They are helped by a trail of cryptic clues left by Sauniere leading them onward.

En route they enlist the help of Langdon's friend Sir Leigh Teabing (Sir Ian McKellen). The clues seem to be pointing towards the legend of the Holy Grail and Teabing is the world expert. In the most infamous part of the book Teabing reveals how the Holy Grail is actually the still-existing bloodline of Jesus, who fathered a child by Mary Magdalene just before he died. Magdalene escaped plots by the early church to kill her and her daughter, fled to France and helped by secret organisation The Priory of Sion the knowledge of all this has remained hidden, but in tact.

En route they enlist the help of Langdon's friend Sir Leigh Teabing (Sir Ian McKellen). The clues seem to be pointing towards the legend of the Holy Grail and Teabing is the world expert. In the most infamous part of the book Teabing reveals how the Holy Grail is actually the still-existing bloodline of Jesus, who fathered a child by Mary Magdalene just before he died. Magdalene escaped plots by the early church to kill her and her daughter, fled to France and helped by secret organisation The Priory of Sion the knowledge of all this has remained hidden, but in tact.Perhaps, the thing that is most intriguing about the film is its the process of adaptation. The movie is fairly faithful to the book, but it's always interesting to see how the film-makers have changed the original work whether for practical reasons (like reduced time), or to eliminate weaknesses within the original work, or to alter why or what it says. Whilst alterations are fairly minimal, all three types exist, and, as a result, have rendered a stronger work of art that the original novel.

There was always a sense with the novel that there was just too much information. Dan Brown had done a fair bit of research, and he wanted everyone to know exactly how much, hence the book was crammed with irrelevant bits of trivia that just felt a bit like someone was showing off. Screen writer Akiva Goldsman has sensibly trimmed many of these excess leaving only the meat of the film's controversial claims.

Furthermore, Goldsman has also removed many of the weakness of the original work. For example the scene where Neveu, a professional cryptologist, discovers the meaning of her name is, mercifully, excluded. Not only does this remove one of the books silliest implausibilities, it also removes that sense of one riddle too many. Most impressively, the film delivers a decent ending - the most disappointing part of the book, is brought up to the standard of the rest of the story in the film.

Furthermore, Goldsman has also removed many of the weakness of the original work. For example the scene where Neveu, a professional cryptologist, discovers the meaning of her name is, mercifully, excluded. Not only does this remove one of the books silliest implausibilities, it also removes that sense of one riddle too many. Most impressively, the film delivers a decent ending - the most disappointing part of the book, is brought up to the standard of the rest of the story in the film.The most interesting type of alteration are the deliberate changes to the ideology of the movie. Lest, anyone gets carried away thinking the film might not challenge Jesus's divinity, or might not bash the Catholic church at every available opportunity, let me be clear. This is still one of the most anti-Christian, and particularly anti-Catholic, films of all time. However it is noticeable that the film tries to soften the blow slightly.

The pivotal scene in this regard is the one in Teabing's study. In the novel, Teabing and Langdon team up to make their outrageous claims. Langdon himself is there to be convinced. Suddenly, all that identification with honest Tom slots into place. We are meant to see these theories through his eyes. Some have seen Langdon's partial conversion to Teabing's theories as evidence that this film is more church-sceptical than the book. I would argue the latter. Brown condescends to his audience such that the novel is almost saying "of course this is all so obvious that we all agree on it don't we"? Director Ron Howard's film puts the audience in the place where they can choose for themselves. Langdon is convinced, we need not be.

The film blunts the edge of the controversy in other ways too. Ian McKellan's performance as Teabing is so wonderfully over the top that he comes across as slightly batty. In the novel, much of what says has already been hinted at or validated by Langdon. When Teabing appears and provides all the answers he fills the role of wise old sage, exposing history's "greatest cover-up" in a way that far surpasses what Langdon is able to offer. In the movie, he is equally as knowledgeable, but somehow he just comes across as an obsessed conspiracy theorist, and (plot spoiler) as we find out he is the villain the question is raised as to how reliable he is.

The film blunts the edge of the controversy in other ways too. Ian McKellan's performance as Teabing is so wonderfully over the top that he comes across as slightly batty. In the novel, much of what says has already been hinted at or validated by Langdon. When Teabing appears and provides all the answers he fills the role of wise old sage, exposing history's "greatest cover-up" in a way that far surpasses what Langdon is able to offer. In the movie, he is equally as knowledgeable, but somehow he just comes across as an obsessed conspiracy theorist, and (plot spoiler) as we find out he is the villain the question is raised as to how reliable he is.The movie also removes some of the book's historical errors, and challenges others, yet at the same time introduces new ones, for example actually suggesting that the pagan Christian violence in 4th century Rome was started by the Christians. Langdon questions that version of history but it's the former that is given the greater weight as it is the version that is shown happening. A little further on though, Hanks' character cites a more realistic (although still shocking) statistic for the number of women killed on suspicion of being witches, and there are various other attempts to remove the film's more glaring errors. It's difficult to know how to respond to this. It's good that these inaccuracies are not being spread further, but unfortunate that some of the more difficult to explain historical distortions are made more plausible.

The other interesting ideological change is in the role of the sacred feminine. In the book this is a key theme. Langdon himself has just published a book on it. But other than the odd mention early on, this theme is conveniently suppressed. For Christian's and Jews alike, the offensive suggestion that pagan sexual fertility rites were practised in Solomon's temple is absent. The level of pagan activity in Sauniere's life is similarly reduced.

The other interesting ideological change is in the role of the sacred feminine. In the book this is a key theme. Langdon himself has just published a book on it. But other than the odd mention early on, this theme is conveniently suppressed. For Christian's and Jews alike, the offensive suggestion that pagan sexual fertility rites were practised in Solomon's temple is absent. The level of pagan activity in Sauniere's life is similarly reduced. Perhaps, most significantly in this regard is the way the role of Sophie Neveu is altered. In the novel, Neveu is a modern, 21st century heroine, beautiful, resourceful brave, but also highly intelligent, matching Langdon step for step with her ingenuity and her riddle solving abilities. Here she is far more the typical Hollywood female. Undoubtedly brilliant, capable of making the male hero look worried, but reduced by the end of the film to little more than something pretty for the boys to look at. Somehow this brilliant cryptographer is unable to solve any of the codes her grandfather left her, despite the fact she has been trained by him, and Audrey Tautou has to settle for staring admiringly as clever Tom Hanks solves all the puzzles.

The other major character whose role is diminished is that of self-flagellating monk Silas - a member of conservative extremist Catholic organisation Opus Dei. He has been charged with destroying the grail at all costs, and we know him to be the murderer from the start. Whilst the film retains much of his perverse self-flagellating, it compresses the story of his past life to a very brief flashback. This reduces Silas (Paul Bettany) to an unsympathetic one-dimensional character. The other Christian characters are similarly one dimensional, and universally wicked that it's difficult to see how anyone could defend the film against the charge of being anti-Catholic.

The other major character whose role is diminished is that of self-flagellating monk Silas - a member of conservative extremist Catholic organisation Opus Dei. He has been charged with destroying the grail at all costs, and we know him to be the murderer from the start. Whilst the film retains much of his perverse self-flagellating, it compresses the story of his past life to a very brief flashback. This reduces Silas (Paul Bettany) to an unsympathetic one-dimensional character. The other Christian characters are similarly one dimensional, and universally wicked that it's difficult to see how anyone could defend the film against the charge of being anti-Catholic.So the film modifies the role of religion in the story, and ends up with a horrifyingly clichéd Hollywoodism "what matters is what you believe". It tries to reduce the offensiveness and controversial nature of the novel, but seems, almost inadvertently, to increase this in other places as well. Visually there is some interesting work, the scene in Teabing's study where he reveals the clues allegedly hidden in Leonardo's Last Supper is a triumph, and there are a few other interesting shots. However, the sense of tension and action that made the book such a page-turner is dissipated - the action sequences are a little dull, and the puzzles are solved a little too quickly. Perhaps it will be this, rather than the swathes of discussion and protests surrounding the film, will be what subjects this controversial story to the confines of history.

No comments:

Post a Comment